Popular running culture tends to reflect the beliefs and priorities of the era that generates it.

Two-Hour Marathon: The Ultimate Time Trial

I keep six honest men,

They taught me all I knew;

Their names were How and Why and When

And How and Where and Who– Rudyard Kipling

This old verse echoes down through the years and is the foundation of any logical system of achievement. The rhyme’s reasoning can also be applied to preparing for and predicting endurance performance by the human race:

- What should be done?

- Why is it being done?

- When should it be done?

- How is it done best?

- Where should it be done?

- Who should do it? (1)

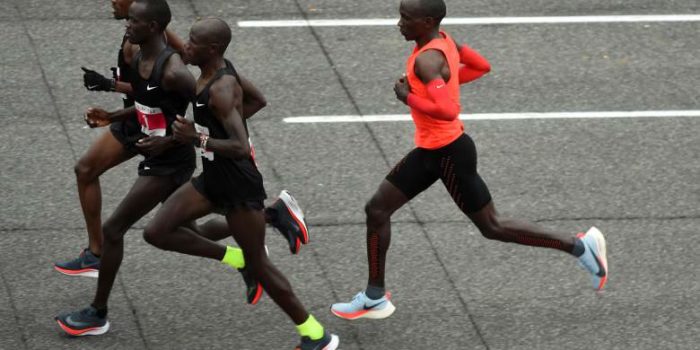

In what some called an unsanctioned branding stunt, Nike sponsors did all the right things to implement a myriad of sophisticated support measures so a super-fast runner nearly pulled off a 2-hour marathon in the first serious attempt of it’s kind at smashing the barrier. Video highlights

The New Holy Grail of Distance Running

The officially recognized world record for the running of a marathon is 2:02:57, – set by Dennis Kimetto of Kenya, at the Berlin Marathon in September of 2014. But the world of running is currently abuzz with a much more recent, and very close to successful – attempt to run this same distance (26.2 miles) in under two hours.

On May 6, 2017 at the Formula One oval in Monza, Italy – in an event sponsored by Nike, three runners completed 17.5 laps of a 1.5-mile circuit. And one of these runners – Eliud Kipchoge of Kenya, the 2016 Olympic marathon gold medalist – came teasingly close to the elusive two-hour mark: He crossed the line at 2:00.25, just 26 seconds shy of the goal, which eclipsed the previous record by more than two minutes.

Runner’s World explains why Kipchoge’s time won’t actually be booked as a world record:

“Although Kipchoge ran more than two and a half minutes faster than anyone else ever has for the marathon, his time won’t count as a world record, because the race didn’t follow two standard rules of competition. First, pacers entered and exited the course throughout the race. Second, the runners received fluids from a moving person (in this case, on a moped) rather than from a stationary set-up.”

To actually break the two-hour mark will require running at a pace of 4:35 per mile, for 26.2 miles, on an approved course. Kipchoge was about one-second per mile off of this pace. Nevertheless, the accomplishment is still a remarkable one, challenging once again our beliefs about what is possible for a human body.

Peak Performance: The Physical Ingredients

How is it that a human body can exceed its previous limits?

The two main physical factors that form the basis of a runner’s performance are power and efficiency. Power refers to how well oxygen is utilized by the body, and is measured in terms of VO2Â max: the maximum volume of oxygen per unit of body weight that the athlete can use in a minute. Though VO2Â max can be increased somewhat by high intensity training, its ceiling is for the most part genetically determined; so unable to be modified except with the use of (mostly illegal) performance-enhancing drugs.

Efficiency has to do with the percentage of the power generated by the runner’s legs that actually translates into forward movement. Changes in technique — supported by advances in exercise physiology — along with high-tech improvements in footwear are strategies for improving efficiency.

The physical layout of a running course can, no doubt, influence a runner’s performance. A downhill course or one that is below sea level (where there’s more oxygen in the air) make for higher efficiency and power, and hence faster times. And finally, strategic use of pacers can have a positive effect on performance: allowing a runner to save energy by running in the pacer’s wake.

Peak Performance: The Mental-Emotional Ingredients

According to one data-driven study on optimal conditions for record-breaking runs, the following physical ingredients are key: cooler weather; a very flat course; intelligent/strategic use of pace-makers for drafting; and larger prize money as a financial incentive.

And what about the runner him- or herself? The so-called “perfect runners” (in terms of their record of success) have in large part come out of East African countries. The dominance of elite Kenyan and Ethiopian runners may in part be attributed to genetics: to inherent bio-mechanical advantages of some sort. But given their historical pattern of success, the continued success is due at least in part to the self-confidence that the previous success has created; along with the benefits of being able to train with and learn from the world’s best runners.

Such ease and fearless confidence are aspects of what’s sometimes referred to as “being in the zone” or in a “flow state”:

“Such a (potentially) record-breaking state of mind requires athletes to enter what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls a “flow state” of deep focus and full immersion in a task mediated by brain chemicals like dopamine and endorphins. And as Steven Kotler points out in The Rise of Superman, among the most powerful ways of triggering these brain chemicals is with group flow, when people are united in the pursuit of a difficult goal, like they are at the training camps in East Africa that have produced today’s top marathoners.”

Mindfulness & Being In The Zone

The experience of a “flow state” or “being in the zone” can be described also in terms of the sort of mindfulness and deep levels of concentration that are familiar to anyone who practices meditation. Moments of mindfulness flow together into an ever-deepening stream of concentration, which can then permeate activities such as running: bestowing great power simultaneously with a sense of effortless ease.

Meditation teacher and accomplished distance-runner Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche makes the connection between body, mind and awareness explicit when he writes:

“The body benefits from movement, and the mind benefits from stillness –The bones and tendons of the mind are mindfulness and awareness. Mindfulness is the mind’s strength, and awareness is its flexibility. Without these abilities, we cannot function. When we drink a glass of water, drive a car, or have a conversation, we are using mindfulness and awareness.” (2)

So deep levels of mindfulness, concentration and awareness are additional ingredients of peak performances: a two-hour marathon, perhaps, if you happen to be one of the world’s most elite runners; or shaving ten or twenty seconds off of your 10K time, which might feel equally miraculous for an age-group competitor.

Also Read:

Mindfulness Meditation and Running

Footnotes

(1) Six searching questions as they appears on page 167 of  Better Training for Distance Runners – by Peter Coe & David Martin – Human Kinetics

(2) Excerpts from Running with the Mind of Meditation: Lessons for Training Body and Mind – Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche

Comments (0)